Stop separating learning from building

In software projects, we sometimes think that we can draw a line between learning and building.

Figure it out first, then execute.

Explore, then exploit!

But when you’re creating new products, that line doesn’t exist. You learn by building. You build on learning. The learn/build ratio shifts over time, sure, but they never really separate.

Many would agree that Waterfall failed because it separated planning from execution. But we keep making that same distinction, only in different ways.

3 ways to draw a line

Most software initiatives share a common goal:

Figure out a great thing to build

Build said great thing

Release the thing

Profit!

After you try it a few times, you realise that the process isn’t quite that linear. There’s uncertainty to grapple with.

We try to groom uncertainty by drawing boundaries. Through the stack, through phases, through scope. But these lines, though well-intentioned, tend to separate learning from doing.

That’s a problem, because learning and doing aren’t separable activities.

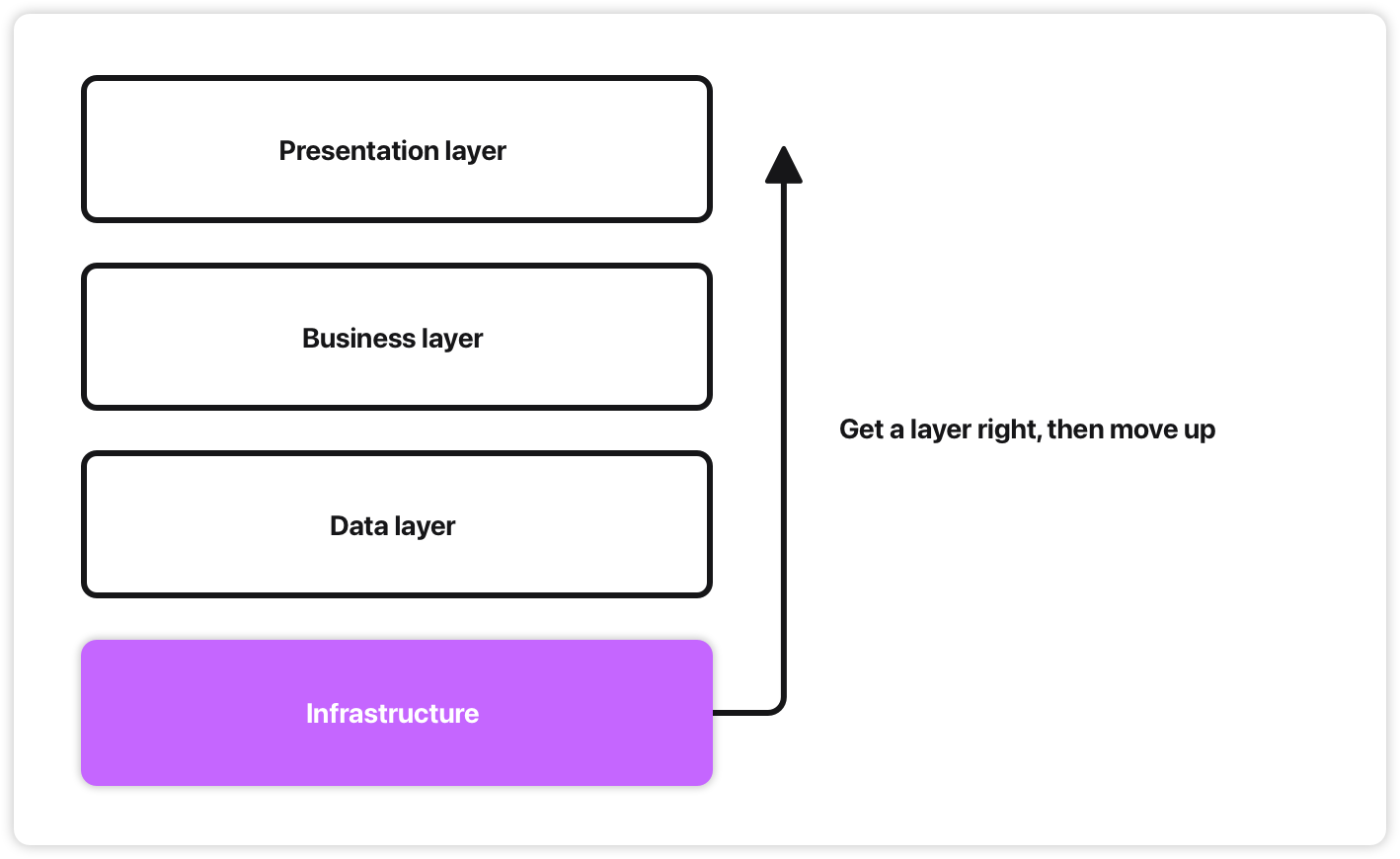

Stack boundaries

You can draw lines through the stack.

Horizontal: layer by layer, bottom-up. Get the data layer right, then business logic, then UI. “Software is like building a house”, so you build the foundations first.

But unless you can anticipate what the final thing looks like, you end up with great foundations for a house you’re not building.

Vertical: feature by feature, left to right. A thin slice through the whole stack: One complete thing you can test and ship.

Vertical is better than horizontal when facing uncertainty. But it doesn’t tell you what to build first. You could slice any feature - which one? And why? Without some ordering principle you end up wasting time on slices that miss the point entirely.

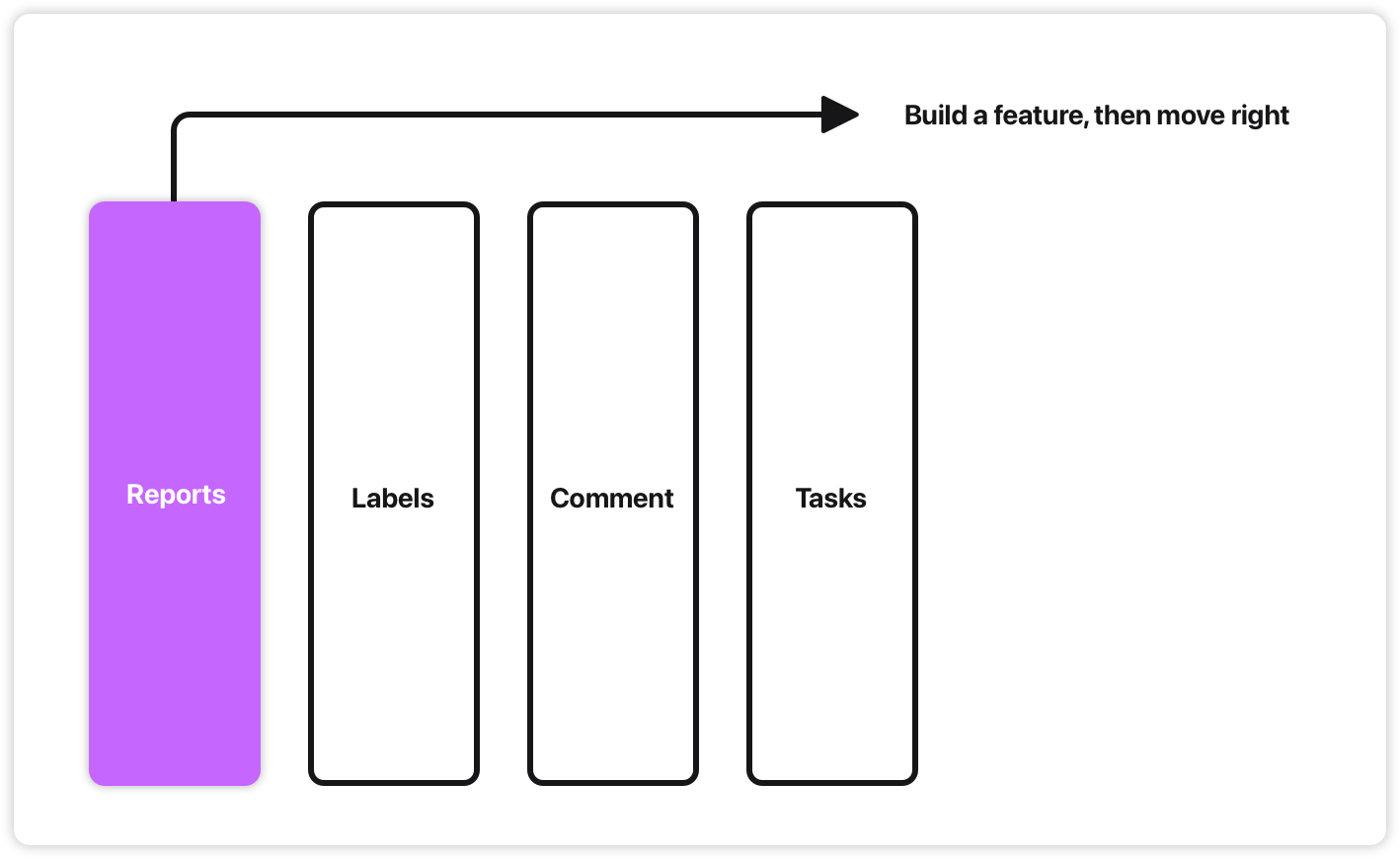

Phase boundaries

You can draw lines through time.

First we learn, then we build, then we test. That’s POCs for you: build a prototype, see if it works, then build the real thing.

POCs often fail in two ways:

It’s too far from real product. The POC environment doesn’t match reality, so the lessons don’t transfer. You throw it away and learn new lessons.

It’s too close to real product. The POC ships, and now you’re maintaining cowboy code in production. That’s no fun either.

You can’t really front-load learning like that. Building real product is how you find out what works.

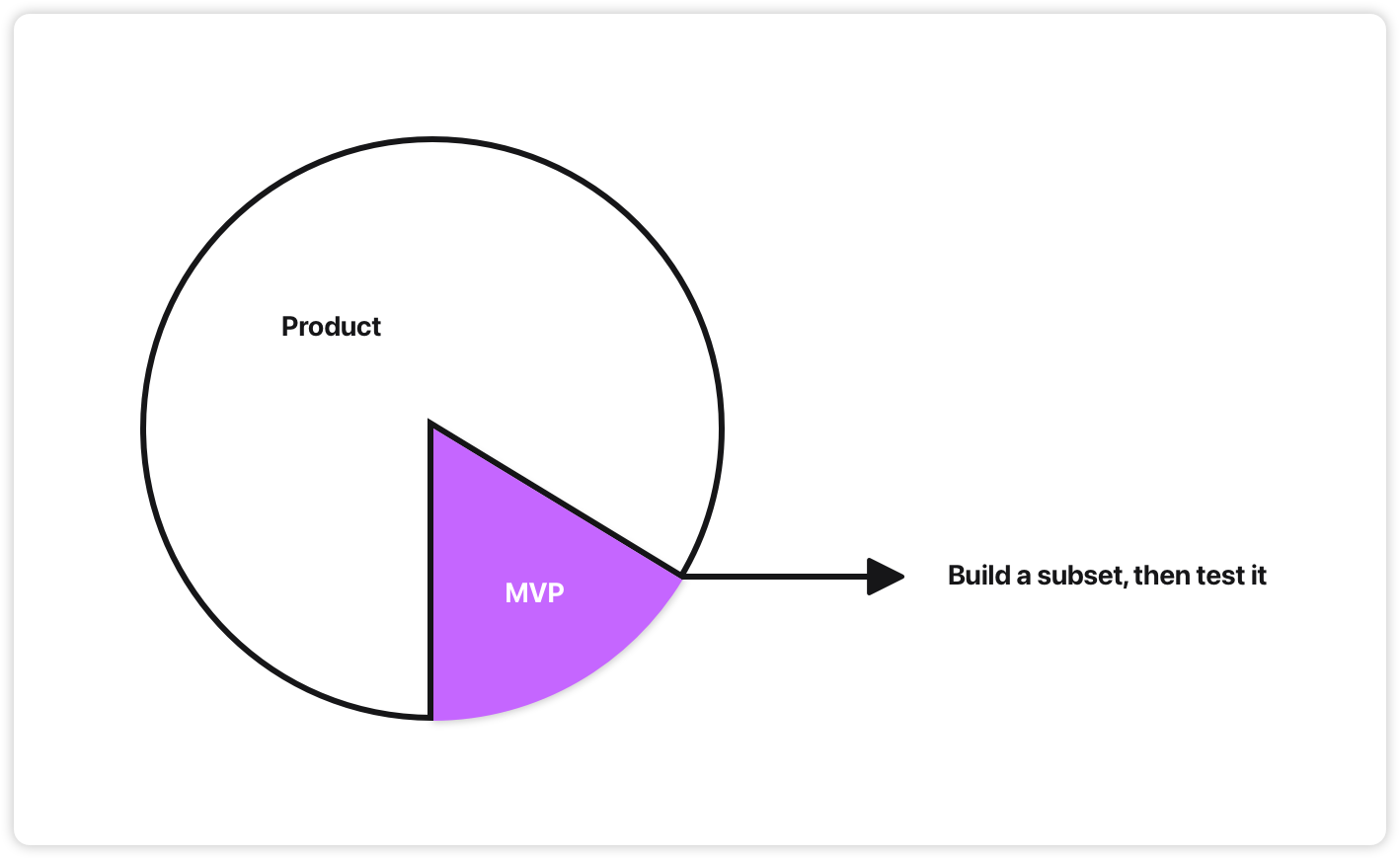

Scope boundaries

You can draw lines through scope.

What’s in scope, what’s out of scope. An MVP: define the “minimum viable” thing, build that, ship it.

But “minimum” according to whom? “Viable” how? Technically, commercially? Viable enough to… uh, learn from?

Too often, the “minimum viable” scope becomes whatever’s in budget. So we reverse engineer the “MVP” from constraints: we have X time and Y €, so the MVP is just whatever fits in that box.

This is deciding how much to build before clarifying what it is.

There is only product

Product is the only tangible thing. You can have more of it, or less of it. Its content can be more or less central to the product idea.

And building real product teaches real lessons.

All three boundaries (stack, phase, scope) try to draw lines through a continuum. But the lines don’t map onto something real. There’s no such a thing as complete knowledge - typically, we’re partially ignorant throughout the entire process. That’s just the reality of creating something new.

So instead of pretending that we can separate learning from building, why not embrace it? Set up the process to maximise learning. Order the work by what teaches the best lessons.

If that sounds like a rehash of what agile practitioners were already saying, well, yeah, it is. Learning fosters adaptation.

The goal is to gain insight for sound software investment decisions. Are we building the right thing? Should we do it differently? Should we stop?

Here’s how I put these concepts into practice.

How I run pilots

Critically, I’ve stopped asking “what’s the scope?” and started asking “what should we do first?”

Start with the big question

The first thing to figure out is what we want to learn. That’s just a question. A good question is answerable just like a scientific hypothesis is falsifiable.

Then we can list out high-level components that mighthelp answer that question.

Order matters

Next, we order the work by:

Centrality: What is most likely to answer the question?

Dependency: What depends on what?

By centrality, I mean: how likely is this work to answer the big question? The most central work is what the whole premise stands on. If it doesn’t work, nothing else matters. If it does, we’ve validated something essential.

By dependency, I mean: some features don’t work without others. We can’t build recommendations without something to base recommendations on.

The first thing we build is the most central component that doesn’t depend on anything else. Then we work outward. What’s the next-most central thing we can do now that we have that? And the next?

We start with the highest learning potential, then expand.

There is no minimum

If we spend all our time on the core premise because that’s where the danger is, that’s time well spent. Either it works out, or we find fundamental flaws. That’s more helpful than building peripheral features.

In this line of thinking, minimum doesn’t exist. Only centrality matters.

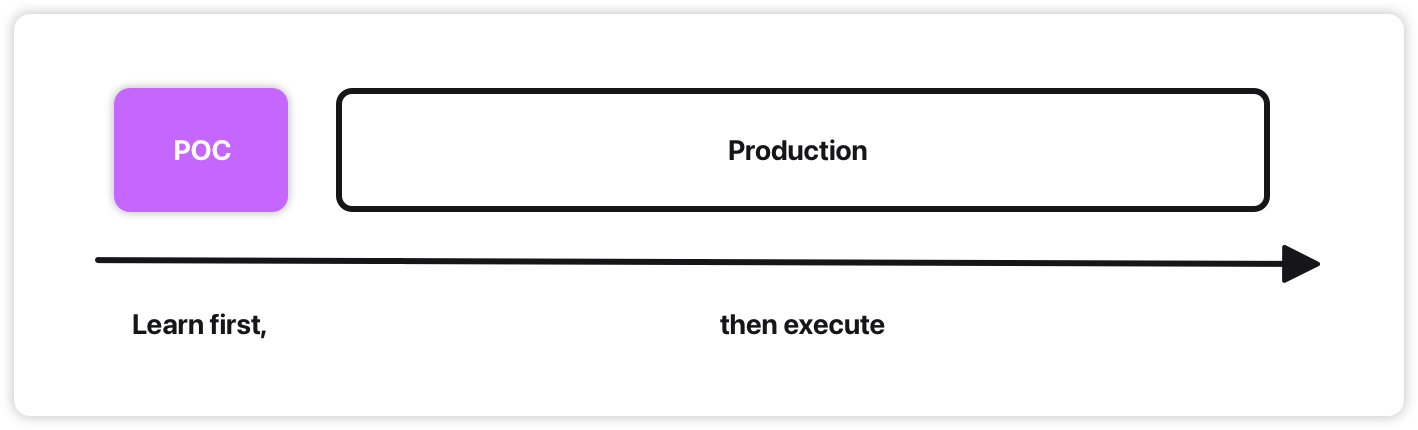

Fix effort, not scope

But planning matters. Budgets matter. You can’t just say “give me infinite time and I’ll build whatever you need.”

A straightforward way to manage that risk is to fix the effort [1].

Fix the time and price. Order by centrality and dependency, then let the scope expand as you go. Build production software from day one [2], and you’ll be happy at any stopping point.

What we learn

Sometimes the solution is hard to find - a signal to stop.

Sometimes it proves viable quickly - a signal to continue.

If we maximise learning about the big question [3], we can make that decision quickly and confidently. Abandon, pivot, or expand.

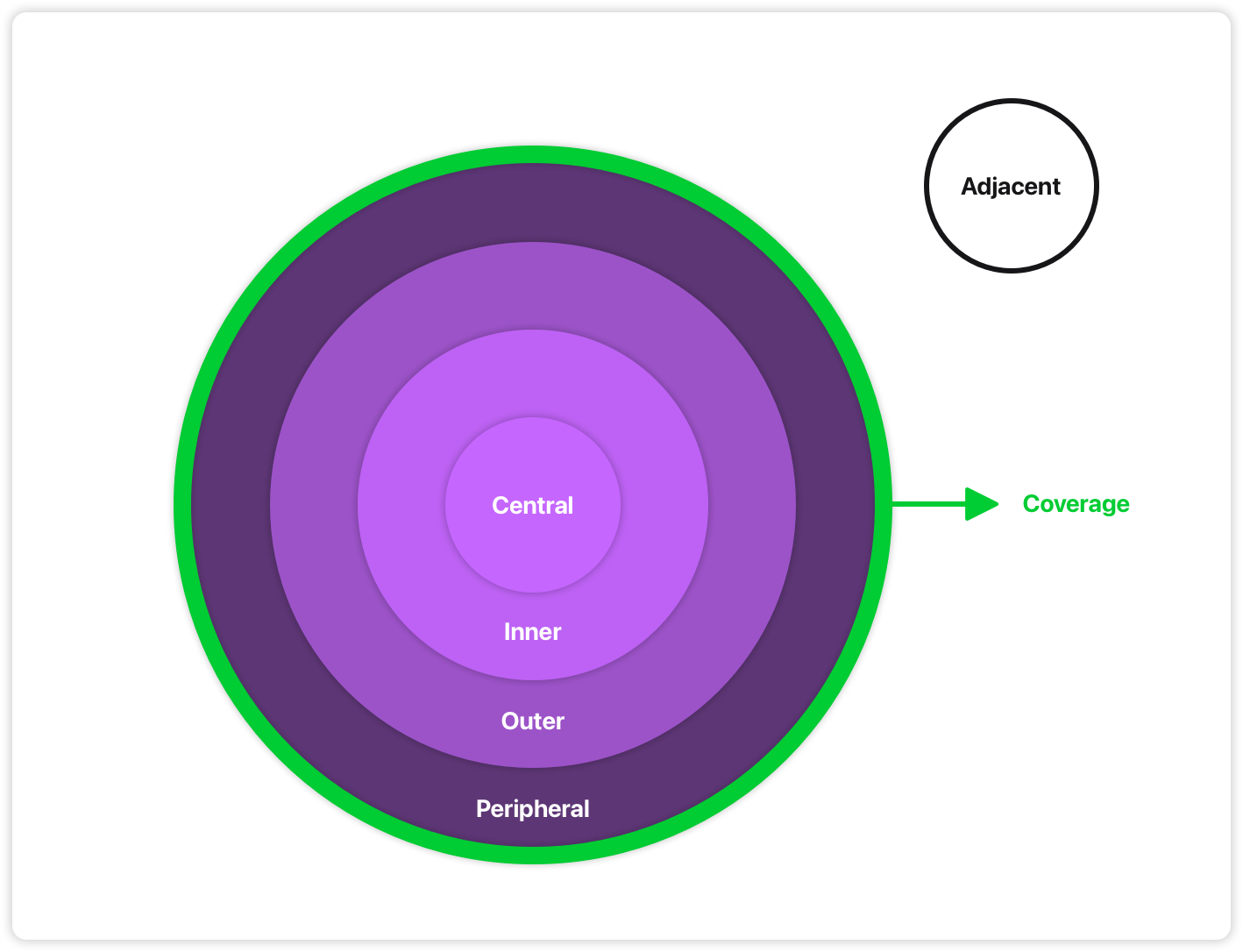

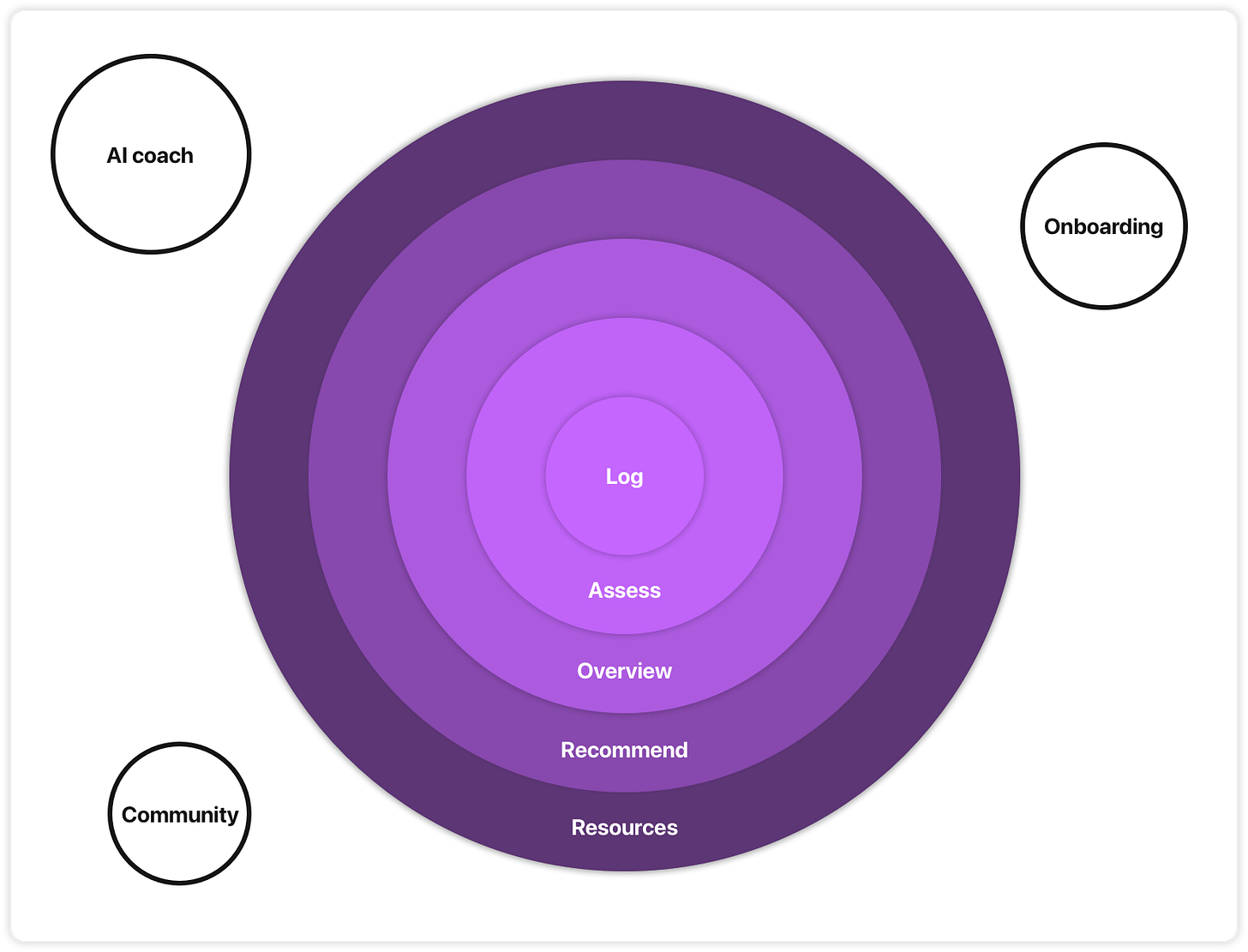

The planets model

To illustrate this thinking, I use a metaphor: planets.

Think of the Earth’s core. The molten center that sustains life on the crust. That’s a central component.

I work in concentric circles from the middle out. Each ring extends outwards from the last. We keep expanding until we’ve covered enough to answer the question.

Coverage is the ground we’ve covered so far. Not a fixed target, but a way to see progress. It grows organically as you move outward.

Adjacent features become “moons”: Smaller ideas orbiting the work. Unrelated questions become other “planets”: work you might tackle later.

This is a way to communicate:

What I’m focusing on

How I order the work

How components relate

How we’re doing on progress

Planets are not a fancy new methodology. They’re just a communication tool; A way I can discuss priorities without pretending to have a fixed plan.

Planets in practice

Let me share a real example to make things concrete.

The project: EnergyMate, an app for post-cancer cognitive rehabilitation.

The question: Can mobile technology help with cognitive rehab by making energy accounting more accessible?

Mapping components: The client had already done a lot of thinking into what the app might do: energy logging, assessments, statistics, community, AI coaching, psychoeducation. Lots of ideas!

Ordering by centrality: Where do we start? With energy logging. That’s the central component. Without energy logging, we can’t test if energy accounting helps and if mobile technology makes it easier.

From there, we expanded outward:

Assessments (to measure progress)

Statistics (to see patterns)

Recommendations (to increase accessibility)

Educational resources (to explain the method)

We focused on iOS, local-first, and left AI features for later. This increased optionality [4] while allowing us to maximise learning about the big question: does energy accounting with a mobile app actually help?

The result: In 6 weeks, we had a working app ready for closed group testing. Real users, data and insights into whether the idea works.

It covers about half of the original vision, but it’s the important half. Complete enough to test with real people. Ready to release and extend: not just a demo.

We managed it in a short timeframe by changing the shape of the problem - ordering the work by centrality.

When it works

I find this way of working effective under uncertainty [5].

You’re working under uncertainty when:

You have incomplete knowledge (don’t know the best solution)

The solution space is unknown (new technology or unproven markets)

System complexity makes outcomes hard to predict

This describes many new software projects.

Working from centrality, you create the conditions to fail fast or succeed quickly. You maximise learning per unit of effort. The work you do is high-impact and unlikely to be thrown away.

More specifically, you create real options to:

Abandon: Filter out bad ideas early

Pivot: Adjust based on evidence

Expand: Invest in working software

If you’re interested in the financial mechanics of real options, I’ve written way more here: https://blog.42futures.com/p/code-economics

When it doesn’t work

If you have complete knowledge, fixed requirements, or you’re working with commodity solutions (all situations with low uncertainty) then just make a plan and stick to it. No need to complicate things.

But lots of software projects aren’t like that.

That’s why I think this mindset matters.

Conclusion

All these words to pitch for a shift.

A shift from asking:

What’s minimum viable?

Should we explore or build?

What foundations do we need?

, to asking:

What’s the big question?

What’s more central to the question?

What depends on what?

I’ve stopped drawing lines through scope, phases, or the stack. Instead, I work in circles: centrality, dependency and coverage.

The planet model helps me do that, and I think it’s a neat way to pritise work in software pilots that maximises learning to minimise risk.

Daniel Rothmann runs 42futures, where he helps technical leaders validate high-stakes technical decisions through structured software pilots.

Notes

[1] Fixing effort while varying scope isn’t a new idea - that’s common sense agile. But it works well when you order by centrality. You front-loaded the essential work, so any stopping point gives you something worthwhile. Compare that to pre-scoping an MVP: if you got the scope right, you’ve done the same thing with more planning overhead. If you got it wrong, you overspend or ship the wrong stuff. Fixing effort keeps all those options open: stop early, continue, or reassess.

[2] By “production software” I mean reliable, maintainable, robust code. You could deploy it and it works. I’m not saying you check off every non-functional requirement from day one. If you have specific needs (compliance, integrations, etc.), you may work them in as you go. The point is to avoid the POC trap of code that’s intended to be throwaway but either ships because “it kind of works” or fails to transfer because it only worked in isolation.

[3] This is like validated learning from Eric Ries’s Lean Startup, but applied to technical product. Lean Startup focused on commercial validation. Do people want this? You might test that with a landing page. For technical product validation we need to go further. Does this actually work? Does the concept hold up? To answer those questions, we need to build working software.

[4] Deferring decisions creates options. By not committing to things that aren’t central to the main question, you keep future paths open. The ability to change direction based on what you learn is valuable, especially early on when you know the least.

[5] Complex systems create uncertainty. Cause and effect is hard to link, so long-term planning doesn’t work that well. Optimization is a better approach: instead of trying to predict the best outcome, you step deliberately in a direction that looks good, assess, and step again. Think of it like navigating terrain: you can’t see the other side of the mountain, so you look at what’s around you and move based on that. Ordering by centrality is a way of picking those first steps.